When I study Luxembourg postal cards, I enjoy the printed backs, the cachets (or “chops”) of the senders, and the auxiliary and manuscript markings applied by the postal clerks. Yet, little has been published on any of these collecting possibilities. It’s a shame.

Is there an unspoken prejudice against printed backs? When asked about the significance of printed backs, a well-known American stamp show judge once told me that show judges were only interested in what the government printed (or otherwise put) on the cards. Rather, the judge seemed enamored of comments on exhibits such as “only one recorded,” “one of three recorded,” and so on—of course, without any reference to “the record” where the pretentious claims could be verified.

In fact, just like postmarks and government-printed indicia, printed backs provide primary data helping us understand the role postal cards played in late 19th and early 20th century commerce, showing notices, orders, invoices, and advertisements. Without an appreciation of printed backs, our understanding of postal card use would depend largely on historians’ secondary accounts.

Here are a few examples:

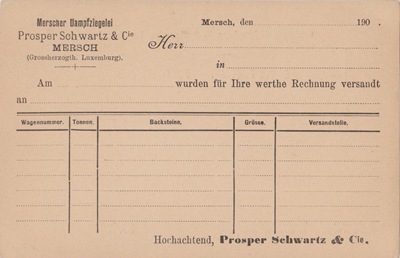

Prosper Schwartz & Cie. Early 1900s |

|

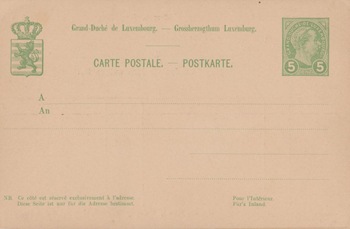

Werling Lambert & Cie. |

|

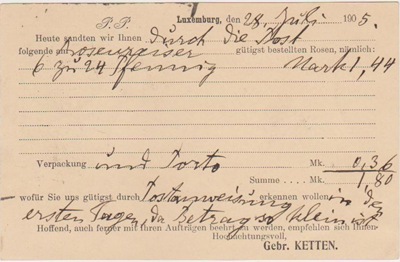

Gebr. KETTEN. |

|

Ch. Bernhœft 1906 |

|

Imprimerie Jos. Beffort 1897 |

|

Breistroff & Schmitt, 1908 |

|

Luxemburger Landes-Dbst und Gartenbau Verein 1920 |

|

No comments:

Post a Comment